Getting Things Done in the Past

!German Speakers — Listen to the podcast episode!

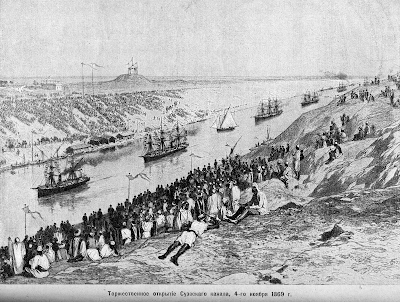

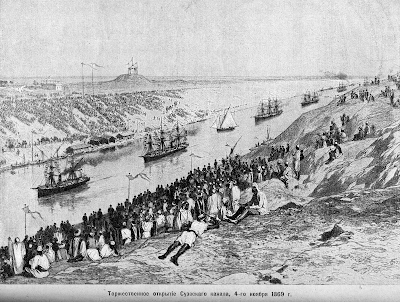

It took ten years to build the Suez Canal in the middle of the 19th century, the same time it took to build the Panama Canal in the beginning of the 20th.

|

| Panama Canal |

The first pipeline was built in the US by Byron Benson in the US. The pipeline was 180 kilometer long:

"They had to surmount very significant and technical difficulties. First, no one had ever built a pipeline this wide. They proposed a 6-inch diameter of pipe. Second, they were building through the Allegheny Mountains which required going up and down very steep valleys and building in the total wilderness.", Britannica

This pipeline was build within one year from 1878 to 1879.

The construction of the Empire State Building is one of the most amazing success stories: With 443m height, it was the largest building in the world until 1971. The construction was done in 18 month from 1930 to 1931.

|

| Empire State Building at construction time |

The Manhattan Project in the 1940s managed to build a nuclear bomb — at a time when the scientific foundation of the field was not yet fully established — within three years. The Hoover Dam in the 1930's was finished in five years, the Golden Gate Bridge (built around the same time) in four. And it took the US eight years — from 1961 to 1969 — to put a man on the moon.

|

| Hoover Dam |

In Austria, the first Wiener Hochquellenleitung, the first Vienna Mountain Spring pipeline was built in the 19th century in four years. It had a length of about 100 km and the grand opening was done by Kaiser Franz Joseph I in 1873. The massive hydroelectric power plant, Kaprun, was built directly after the devastations of World War II, in eight years between 1947 and 1955.

|

Fountain on Schwarzenbergplatz in 1873, where

Kaiser Franz Joseph celebrated the opening of the

Vienna Mountain Spring Pipeline |

And most impressively: during the 1970's, through the Messmer plan, France built 56 nuclear reactors within 15 years, many of which still deliver reliable and carbon-free electricity and are key to our energy survival this winter in Europe.

|

| French Nuclear Power Plant |

But surely we must be much faster today, given all the innovation we have achieved since?

China has indeed seen similar achievements more recently. The Three Gorges Dam was built in eight years, and the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, with a 55 km-length, the longest open-sea fixed link in the world, was built in nine years.

|

| Three Gorges Dam |

But when we look at the infrastructure and building projects of recent years in Europe and the US, the picture looks all but rosy. Just a handful of examples: the construction of Elbharmonie (a concert hall in Germany) took nine years to complete, and the cost exploded from €200 million to nearly €900 million. To put this into context: we needed the same time to build a concert hall, as our forefathers needed to build the Panama or Suez Canal. More importantly though, there are probably thousands of concert halls around the world to serve as precedence, whereas the Panama Canal was a construction unprecedented at the time.

Speaking of run-of-the-mill projects, take airports around the world: there are roughly 500 in France, Germany and the UK, 900 in Argentina, 14,000 in the US, even 17 in Antarctica. One would be forgiven for thinking we know how to build airports by now. And yet, the building of the Berlin airport took 14 years and created massive cost overruns. It is not even clear whether it can ever be operated economically.

This is not only a German phenomenon: while we built the first mountain spring pipeline for Vienna of 100km length in the 19th century in four years, the Semmering-Basistunnel, a tunnel project in the mountains close to Vienna, with a length of 27km, is under construction since 2012 and is supposed to be finished in 2030, after 18 years of construction. When Finland undertook to extend one of its nuclear power plants, the Olkiluoto Block 3, the schedule and cost estimations were constantly overrun. Current estimates put its completion at this year (2022), after 17 years of construction. To put this into context: France built not one but 56 power plants in a shorter time.

In terms of energy supply we even seem to go backwards: opposed to the grand promises of “Energiewende”, Germany is burning more coal today than it did in the last years.

Can these be dismissed as mere freak examples? A recent New York Times article suggests otherwise:

- The construction of the Honolulu rail transit with a length of 32 km started with an estimated cost of $125 million per km — $4 billion in total. And if this initial estimate in 2006 was not crazy enough for building a railway, the cost estimation now stands at more than $11 billion, with a planned completion by 2031. Should this estimation hold, it will have taken 25 years to finish a rail track of 32 km with a cost of roughly $350 million per km.

- In 2008, California started a high-speed railway construction to connect Los Angeles to San Francisco with estimated costs of $33 billion. Construction was due to finish by 2020, in 12 years. Current estimates place the project completion in 2033 and the costs at $100 billion.

- The New York East Side Extension was planned to commence in 2006 and finish in 2011, with a budget of $2.2 billion. It now stands at $11 billion, with the completion estimated for December 2022.

Joseph Schofer, a Northwestern University civil engineer quoted in the article says »In the world of civic projects, the first budget is really just a down payment”, and Ronald N. Tutor, chief executive of Tutor Perini, a California firm that is building some of the nation’s largest projects, confirms that “All the major projects have cost and schedule issues”.

And as a last rather astounding example: in San Francisco the building of a public toilet was finally cancelled, after the planned toilet was estimated to cost $1.7 million.

Luckily the software world is all efficiency and innovation!

We could theorise that there is something particularly difficult about building infrastructure in the real world and that it becomes harder every day. But surely in the virtual world of software everything is fast, smooth and efficient, with one innovation overtaking the next. Or is it?

The term software crisis was coined in the 1960's and the situation has not improved since. Contrary to our perception that information and communication technology (ICT) is moving fast and reinventing itself all the time, this is not true behind the scenes. Just some examples for illustration. All of these issues are, on an engineering level, comparable to building the Golden Gate Bridge with such serious flaws that would cause it to collapse a year later:

Not only do we suffer from a dramatic lack of quality in our ICT infrastructure, but we are also facing enormous maintenance costs and a large number of failed IT projects. One of the largest failures in Europe in the last years (but by no means the only one) was the SAP transformation at Lidl which was terminated after €500 million were sunk in the project.

Such incidents occur frequently. The bottom line is: we do not seem to have our ICT systems or infrastructure projects under control, which leads to security issues, data breaches and — more to the point of this article — massive cost and schedule overruns within the IT projects, but also increasingly bleeding into other infrastructure projects.

Why this is of utmost importance

The capability to build essential infrastructure like railways, bridges or nuclear power plants quickly and in reasonable quality is fundamental for a modern society, especially one that is facing a number of severe challenges. Should we, for instance, have serious intentions to decarbonise our economy, we need one Messmer-plan-like nuclear build after the other. And that at least at the level of speed and quality that France delivered in the 1970's and 1980's.

We have to move fast on multiple fronts:

- restructure our energy infrastructure

- onshore manufacturing again

- de-globalise supply chains to a certain degree

- modernise agriculture by utilising biotechnology, vertical farming, etc.

- maintaining and rebuilding infrastructure that we have neglected for decades.

All these activities could be a net positive for our economies and environment, provided that they progress reasonably fast and efficiently.

While classic economic liberals and environmentalists usually do not have much in common, but many seem to share this idea, that we can quickly improve our situation through innovation, and the implementation of entirely unproven or speculative technology. One side might be thinking of machines that suck carbon out of the atmosphere and of creating economic growth by floating the market with innovations; the other of Rube Goldberg-like machines distributed over continents that allow wind and solar power to replace fossil fuels, and build a hydrogen economy along the way.

Both are betting on technology that is not yet available or entirely unproven. This bet is off the table, if our capabilities to innovate and even to build conventional infrastructure is not on par with expectations.

Contemplating causes

While we huddle in teams, attend design-thinking workshops and run extensive stakeholder consultations to debate even the slightest risk that could in theory occur in any given undertaking, important progress and transformation in the outside world seem to be standing still, and real existential risk building up. Why is it, that we don't seem to be getting many important things done any more, at least not with reasonable efficiency?

I believe that there is — as in all complex problems — not a single cause, but a number of intertwined ones. I will try to outline some factors that I believe to contribute substantially. Yet, please consider it not an exhaustive analysis , but rather a call for discussion.

I would welcome any comments that agree or disagree with these observations.

1 Digitisation Disappointment and General Stagnation in Research and Technology

I find it quite remarkable, even if this is not sufficiently discussed in public, that although digitisation was promised as a booster for productivity, the opposite seems to have happened. Several prominent experts have written and spoken about this phenomenon, among them Tyler Cowan, Robert Gordon, David Graeber, and Peter Thiel.

Robert Gordon remarks that productivity gains between 2004-2012 were on the lowest point since the end of the 19th century, which is remarkable, considering that this was the time when digitisation accelerated.

Tyler Cowan writes:

“the low-hanging fruit has been mostly plucked, at least for the time being. […] The Great Stagnation continues and indeed worsens, driven by an increasingly dysfunctional politics.”

Gordon's article and Cowan's book are both around ten years old, but not much seems to have changed since. The Covid pandemic and the current energy crisis only appear to have worsened the problem. Even before the crisis, other critics told the same story. Peter Thiel in a conversation with Eric Weinstein in 2019 said:

“stagnation started in the late 1970s, with exception of digital technologies; even within Silicon Valley things seem to slow in the last 7 / 8 years” and “I don’t think the Truman show can go on for longer than a decade”

Until now the situation has not shown any signs of improvement. Even the anarchist activist and influential public intellectual David Graeber surprisingly seemed to agree with Peter Thiel's assessment, in his book Bullshit Jobs as well as in a discussion with Peter Thiel in 2020 (Where did the Future go?):

“the pace at which scientific revolutions and technological breakthroughs occur has slowed considerably since the heady pace the world came to be familiar with from roughly 1750 to 1950 […] and in most wealthy countries, the younger generations can, for the first time in centuries, expect to lead less prosperous lives than their parents did.”

Finally, I would like to quote Nicholas Bloom, who describes the fast decline of scientific performance over the last decades:

“research effort is rising substantially while research productivity is declining sharply. […] it takes around 13 years for research productivity to fall by half. Or put another way, the economy has to double its research efforts every 13 years just to maintain the same overall rate of economic growth.”

So, getting nothing done is also a phenomenon in science, albeit with a different spin. I assume that the stagnation we experience and described here is a contributing factor. I believe it is driven by two factors: (1) the low hanging fruit are plucked and new technology is much harder to come by and (2) we are experiencing a fast degeneration of research quality, hiring and promoting of scientists at universities due to bureaucratisation of research, massive flaws in science funding, and lack of critical exposure of scientists to the real world.

“Academia has a tendency, when unchecked (from lack of skin in the game), to evolve into a ritualistic self-referential publishing game.”, Nassim Taleb

Sabine Kleinert and Richard Horton write in a Lancet commentary:

“There is clearly a strong feeling among many scientists, and not only Nobel Prize winners, that something has gone wrong with our system for assessing the quality of scientific research.”

This does not only lead to an increasing amount of irrelevant science and science of questionable quality, it also brings a massive overhead and waste of academic bureaucracy and funding infrastructure with it:

“European universities spend roughly 1.4 billion euros a year on failed grant applications—money that, obviously, might otherwise have been available to fund research. […] I have suggested that one of the main reasons for technological stagnation over the last several decades is that scientists, too, have to spend so much of their time vying with one another to convince potential donors they already know what they are going to discover.”, David Graeber

2 Regulations, Bureaucracy and Focus Loss

It seems obvious that as a society we need to regulate certain technologies that can have dangerous effects, and harm the environment, economy or society. But over the decades, regulation and red tape have become more and more extensive with increasingly dubious results. Regulating complex topics is very hard, and rarely done well. Gerd Gigerenzer provides examples of financial regulations to illustrate this point:

- Basel 1 (1988): 30 pages, calculations could be done with “pen and paper”; 18 pages primary law in the US — was allegedly too simple

- Basel 2 (1996): more than 300 pages (did not stop the financial crisis of 2008)

- Basel 3 (2009): more than 600 pages; more than 1.000 pages primary law in the US; consequences of these regulations are hard to understand and require specialised firms

The idea that complex problems need overly complicated regulations seems to be a fundamentally flawed one. More and more complicated regulatory frameworks help large market players and keep startups out of the market, they also allow experts to find esoteric holes that can be exploited and are counter to the original intentions. Far from making things safer, they often make things more complex and less safe, slowing down progress dramatically.

“Indeed much of the work of investment banks in my day was to play on regulations, find loopholes in the laws. And, counter-intuitively, the easier it was to make money.”, Nassim Taleb, Skin in the Game

Marc Andreessen also talks about stifling stagnation and describes this phenomenon with the example of two major political projects of Richard Nixon's: One was the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate the environmental impact of corporations, and the other was Project Independence — the Nixon-era nuclear roll-out programme. Analysis showed back then what we also know today, that nuclear energy is the cleanest, safest and best technology for producing energy. Based on this, 1,000 reactors were supposed to be built until the year 2000 in the US. That did not happen. “We got the regulation and stagnation but not the reactors.” Andreessen concludes.

David Graeber describes in The Utopia of Rules stagnation in our society and progress, but also a more unexpected consequence — computers became amplifiers of bureaucracy:

“The Internet is surely a remarkable thing. Still, if a fifties sci-fi fan were to appear in the present and ask what the most dramatic technological achievement of the intervening sixty years had been, it's hard to imagine the reaction would have been anything but bitter disappointment. […]

Computers have played a crucial role in all of this. Just as the invention of new forms of industrial automation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries had the paradoxical effect of turning more and more of the world's population into full-time industrial workers, so has all the software designed to save us from administrative responsibilities in recent decades ultimately turned us all into part or full-time administrators.”

And finally Graeber writes in Bullshit Jobs:

“The most miserable thing about box-ticking jobs is that the employee is usually aware that not only does the box-ticking exercise do nothing toward accomplishing its ostensible purpose, it actually undermines it, since it diverts time and resources away from the purpose itself.”

and maybe very important for the considerations here:

“much of the reason for the expansion of the bullshit sector more generally, is a direct result of the desire to quantify the unquantifiable. To put it bluntly, automation makes certain tasks more efficient, but at the same time, it makes other tasks less efficient.”

So, did we use computers to automate the wrong things? To maximise distraction, support unnecessary bureaucracy while at the same time harming our capability to get things done?

3 Fear-driven Management and Juridification of Society

All this goes hand in hand with what I call the rise of fear or liability-driven management, which blossomed with the steady rise of the managerial / administrative class. In my experience there is often a substantial difference in decision making between founders/entrepreneurs and professional managers. The first group is deeply invested in their company, by definition holds in-depth knowledge (otherwise the company would not have survived) and makes active decisions, that is with mid- and long term prospects of the company in mind, driven by facts, taking risk.

The managerial class on the other hand, more often than not, has a different priority: themselves. The question of management is reframed from: what is best for the company to how do I survive the next years while maintaining this salary and this position (or higher). As a consequence, decision making tends to be passive, risk-averse (as far as their own risk is concerned). This leads to an over-reliance on legal and professional consulting, which not only costs a lot of money but more importantly throws a spanner in the works.

“The final victory over the Soviet Union did not really lead to the domination of the market: More than anything, it simply cemented the dominance of fundamentally conservative managerial elites-corporate bureaucrats who use the pretext of short-term, competitive, bottom-line thinking to squelch anything likely to have revolutionary implications of any kind.”, David Graeber

Hand in hand with this trend of defensive and risk-avoiding decision making goes a juridification of society. As mentioned above, regulations get more and more complicated, old rules are hardly removed but new one are constantly added. As the Austrian lawyer Lukas Feiler explains in a talk:

“The interesting puzzle really is, how did we end up with such a complex legal landscape, when we all agree that it is simplicity what we would need. […] Moreover, politicians act on problems of the past. […] It is, as if politicians are driving a large truck by only looking into the rear mirror.”

So it seems, not only are we making our legal system unnecessarily complex, we also react to problems of the past, slowing progress down, while overlooking the actual risks of the future.

4 Specific Loss of Capability to Build Large Projects

And finally, after the more abstract considerations, we have witnessed a de-industrialisation of Western nations, which has even been lauded by pundits of different political affiliations. Market liberals saw it as an efficiency measure, and environmentalists were happy to get rid of heavy industry. The former did not consider that short-sighted efficiency measures had to be paid back with high interest rates in the future. The latter overlooked that we merely exported our polluting industry to other nations and more importantly, our know-how with it. If we don't maintain and build certain industries any longer, if we do not train new engineers, we will lose the capability to build related large projects.

The good news is that many of the successful and fast projects from the past were built without a lot of prior knowledge. So, with enough determination, there should be no reason why it should not be possible to quickly rebuild this capacity again.

As far as ICT is involved, we got entangled in a complexity trap. Over time, we improved our skills to make software, but we did not use these skills to build software better, but to constantly build more complex software that actually overburdened us. This is a serious problem, because software is the digital nervous system of our society and also of modern infrastructure. Having lost control over large parts of this digital infrastructure must have harmed large infrastructure projects in one way or another.

What next?

Firstly, I would like to test, debate and discuss the observations made in this article and would welcome your comments. Secondly, the fact that we experienced these achievements in the past shows that we are capable of building large infrastructure fast and reliably. We might have lost that now but a better understanding of the reasons could bring us back to where we were. This is the good news. The bad new is, if the Western world will not do it, other nations will, to our disadvantage. So as a next step, more concrete ideas have to be developed on how to improve the situation. I think solutions will have to consider the following aspects:

- Ensure that managers and politicians have skin in the game

- Reward risk taking to a certain degree, not defensive decision making

- Decidedly remove unhelpful bureaucracy and red tape

- Rethink science funding fundamentally

- Aim for generic and simple, not complex and specific legislation (or rules in general, this also applies to corporate processes and the like)

- Allow failure, iterate, while paying attention. Keep going and adjust with new learnings

Final Remarks and Possible Objections

One possible objection to this article could be that I am cherry picking examples. The examples I have found seem to be too common to dismiss as exceptions to the rule. The New York times article also points to the same findings. But if you believe otherwise I would be interested in receiving your comments.

One could also criticise that the historic projects are not really comparable to modern ones, given that the working conditions during the construction of, for example, the Panama or Suez canal 100 or 150 years ago were certainly not up to modern labour-standards. Yet, even with complying with modern labour standards, shouldn't we be easily able to compensate the potentially slower progress of non-exploitative methods of working with supposedly vastly superior technology, equipment and computers?

It is also important to note one constraint in my selection of examples: I explicitly did not choose examples of modern undertakings that are especially innovative or have not been achieved so far (though hyped by some and dismissed by others), for example uploading the brain into the computer, colonising Mars, nuclear fusion power plants or the like. One could easily argue that these types of projects are inherently much harder than building a canal or a dam.

In this article I am referring only to construction scenarios that we have done repeatedly in the past like dams, railway lines, bridges, opera houses and even nuclear power plants. For context, globally about 450 nuclear power plants are in operation today, and even more were built in the past or still under construction. So I chose infrastructure projects that are the opposite of new, and existing everywhere around us already.

One last note: The projects I have highlighted in this article were not selected because they are necessarily useful or ethical, but only for their engineering and management prowess.

.jpg)

.jpg)